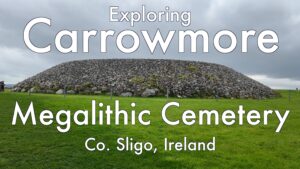

Ireland’s distant past speaks to the present at Carrowmore Megalithic Cemetery.

Located on the Cúil Irra Peninsula on Co. Slio, Ireland, Carrowmore is the oldest and largest group of megalithic tombs in Ireland. It is also one of Europe’s largest megalithic cemeteries.

Thanks to extensive archeology, historic documentation, advanced scientific analysis and recent preservation efforts, Carrowmore provides a window into who the Irish of 3500 BCE were and what they were up to.

Carrowmore is set within a spectacular megalithic landscape dominated by the mountain of Knocknarea to the west. On Knocknarea’s summit is one of Ireland’s largest cairns, known as Queen Maeve’s Cairn.

There are bout 50 megalithic tombs on the Cúil Irra peninsula. Most of these, 30 tombs, are at Carrowmore.

Carrowmore’s tombs were built from 3500 BCE to 2900 BCE, during the Neolithic, New Stone Age, according to radio carbon dating results. It’s likely people who built the tombs were Ireland’s first farmers.

Carrowmore is one of Ireland’s ‘big four’ megalithic clusters along with nearby Carrowkeel in Co. Sligo and Loughcrew and Brú na Bóinne in Co. Meath.

Archaeologists consider Carrowmore – like Newgrange, Loughcrew and Carrowkeel – part of the Irish Passage Tomb Tradition.

There may have once been as many as 100 megalithic monuments in the Carrowmore area. Many of the tombs were destroyed or damaged during the during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries by quarrying, field clearance and by antiquarians hunting for ancient treasures.

A number of monuments are located on private property adjacent to the public National Monument.

Today Carrowmore is a protected Irish National Monument and is maintained by the Office of Public Works.

Extensive Research

Although many of the monuments have been disturbed, Carrowmore has been the subject of extensive research.

Dutch artist Gabriel Beranger visited Carrowmore in 1779 and drew some of the monuments. A valuable record of Carrowmore at the time, his drawings monuments since destroyed or damaged.

Pioneering photographers, such as W.A. Green and R.J. Welch of the Belfast Photographer’s club, photographed Carrowmore at the turn of the twentieth century.

Local landlord Rodger Walker conducted unrecorded antiquarian excavations in the 19th century. These digs were essentially treasure hunts to augment Walker’s antiquities collection. Walker kept poor records of his activities. Some of the Walker’s finds are now at Alnwick castle in Northumberland, England.

The Carrowmore monuments were mapped and numbered by Irish archeologist George Petrie in 1837 during the first mapping of Ireland conducted by the British Ordinance Survey. Petrie’s number system identifies the monuments today.

In the 1880s Sligo-born archaeologist and army officer Col. W.G. Wood- Martin conducted the first recorded excavations and made numerous finds.

Extensive excavations led by Swedish archaeologist Göran Burenhult were conducted from 1977–1982 and 1994–1998 and 10 tombs were fully or partially excavated. Listoghil, Tomb 51, was excavated in 1996-1998.

At least two sets of archeologists have conducted extensive research on Carrowmore’s age using radio carbon dating and studies of nearby lake sediments. Carrowmore’s monuments were found to span the era from 3750 BCE to 3000 BCE and the builders were farmers.

Multimillenia-old human remains found at Carrowmore have been able to tell their story thanks to DNA analysis.

Intimate connections between occupants of other Irish passage tombs have been revealed by DNA derived from human bones found at Carrowmore. A detectable kin relationship was found between a male buried in Listoghil, Carrowmore’s Tomb 51, and three other males buried in Newgrange, Millin Bay and Carrowkeel.

This DNA relationship points to the existence of a sophisticated interrelated hereditary elite that could inspire the creation of increasingly large and complex tombs and ritual sites across a wide portion of Ireland. In a time before Stonehenge or the Egyptian pyramids, an Irish farming-based society without cities managed to use stone, bone and wooden tools to build religious monuments that have defied destruction and still retain their place in the landscape.

Modern scientific analysis of ancient genetics proves the ancestor of the people who built Ireland’s megalithic monuments originated in Anatolia, in what is now Turkey.[12]

Carrowlmore is the megalithic site keeps on giving for archeologists doing the digging.

In 2019 a team of researchers led by Marion Dowd and James Bonsall of the Institute of Technology Sligo uncovered feature unlike any other seen in Ireland.

The Sligo team conducted geophysical surveys at the Carrowmore megalithic complex, finding a circular structure that was away from where tombs have beeb found. The feature was thought to be a barrow, a circular earthen monument surrounded by a ditch.

Once the team put trowels to the soil something unexpected emerged.

“Our survey revealed several features that were not visible above ground,” Bonsall said in an article in the publication Archeology. “We discovered that the ‘barrow’ contained a central pit and a substantial circular ditch.”

A sunken area within the layer of stone contained black, charcoal-rich soil, Dowd said in Arecheology.

“So far, we cannot find any parallel for it in Ireland,” Dowd said.

Listoghil or Tomb 51 – Carrowmore’s Focal Point

Listoghil was built circa. 3500 BCE and is 34 metres in diameter. It the only cain at Carrowmore.

It has a distinctive box-like inner chamber.

The front edge of the entrance covering stone has marks that may be the only megalithic art at Carrowmore.

Three large boulders were found beside the central chamber. Under the cairn may be the remains of a destroyed passage or of a megalithic construction that predates the cairn.

Many of the satellite tombs face the central area. Tomb 51’s location appears to have been the cemetery’s focal point.

Unburned bones as well as cremations has been found in Listophil.

The alignment of Listoghil points at a low saddle-like formation 6.5 km to the east-southeast in the Ballygawley Mountains. The alignment coincides with sunrise at the start and the end of winter, important seasonal festivals in the Gaelic calendar.

Satellite tombs

Corrowmore’s monuments originally consisted of a central dolmen-like megalith with five upright orthostat stones with roughly conical capstones on top enclosing a small pentagonal burial chamber. These tombs were each enclosed by a boulder circle 12 to 15 metres in diameter.

The boulder circles contain 30 to 40 boulders. The stone monuments are usually made with gneiss, the stone material of choice for the tombs. Some tombs have a second, inner boulder circle.

Entrance stones (or passage stones, crude double rows of standing stones) extend from the central feature, showing the intended orientation of the dolmens. The monuments generally face towards the area of Tomb 51, the central cairn. Four monuments are in pairs.

Each monument was built on a small level platform of earth and stone. Stone packing surrounding the base of the upright stones that locks them in place is one of the secrets of the dolmens’ longevity.

Irish folklore dates Carrowmore’s tombs to Ireland’s mythology and the Battle of Magh Tuireadh, where the Firbolgs were defeated by the Tuatha De Danann.

Carrowmore’s ritual landscape may have taken on new meaning long after the original builders of the monuments were long gone. Archeological evidence suggests tombs that during the later Bronze and Iron Ages some tombs rebuilt and reused.

What to know if you visit Carrowmore:

Admission is 5 euro.

Open May to September 10:00 to 5:00

There’s parking lot on the south side of the road adjacent to the visitor’s center. Parking is free.

It’s worth spending a few minutes in the small museum in the visitor’s center, especially if you are visiting the site with young people.

Allow at least an hour to explore. The views of the surrounding area alone are work the walk around the site.

A two-sided, laminated map and guide to the site is available at the front desk of the visitor’s center for a REFUNDABLE 2 euro. Get the map. You’ll be glad you did.

Although the site is mowed and generally open it is not wheel chair friendly. People with mobility issues who walk with a cane or trekking poles may be able to access some of the site, particularly the North Walk, which is smaller and more level than the south side. Caution is advised at all times.

DO NOT climb on any of the monuments.

The are bathrooms with changing tables.

In the summer months there is a good coffee cart next to the visitor’s center.